Table of Contents

Why I hate being a tourist

To really experience a culture, I learned you need to slow down and engage with locals

I never wanted to be “merely a tourist.” I always wanted a more immersive experience of travel. And as a blogger and travel writer, I have always tried to learn as much as I can about India and the other destinations I visit, and show respect for the culture in my writing. These are important values to me.

I’ve thought about my responsibility as a travel writer a lot. I feel that sensitive travel stories, told with understanding and insight, and carefully curated tours that encourage visitors to experience local culture, can help humanize “other” cultures and bring the world together. They can make the world smaller, and the “other” seem less foreign and more familiar.

UPDATE JUNE 2021: In the midst of the coronavirus pandemic, many people are rethinking tourism — and the systemic structures that govern it. I was recently very excited to read this article about how Bali is rethinking tourism before reopening. They are questioning the “tourist gaze” and dependency on foreign income that erodes their own culture. I love the idea of tourism that preserves the local culture and remembered that I once wrote about this subject, 10 years ago, before I really knew anything about tourism.

When I originally wrote this post in 2010, I was just starting out as a professional travel blogger, and trying to come to grips with the concept of tourism. I didn’t have a tourism background at all — I started travelling in 2005 to overcome depression, and started blogging to keep in touch with my family while I spent six months criss-crossing India. Travelling and travel blogging eventually became my lifestyle, then my career. It was a slow, organic evolution … but I was always a little uncomfortable with several aspects of tourism. I have often said I’m surprised I ended up in tourism as I hate being a tourist.

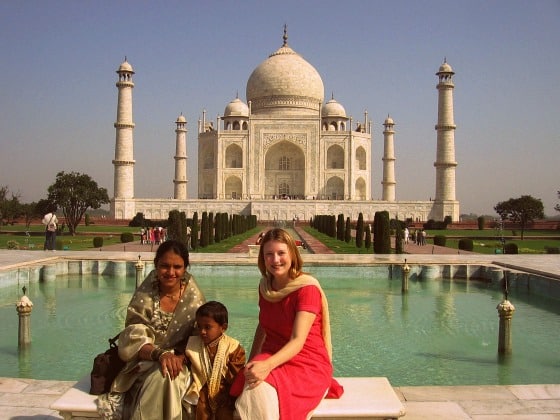

In 2005, I came to India to immerse as much as possible in the culture, to study Yoga, to learn about both myself and India, to overcome depression, to grow as person, and to gain much-needed global perspective as a middle-class Canadian. I lived with an Indian family in Delhi (my boyfriend’s family) and when I travelled, I found I was uncomfortable in the tourist hot-spots and backpacker ghettoes. I carried a Lonely Planet guide with me for information, but increasingly came to learn to AVOID the places it touted.

I felt these places perpetuated a post colonial attitude towards the locals, where foreign backpackers hung out with other foreign backpackers and didn’t seem interested in getting to know the local culture or customs. They seemed to just want a cheap place to hang out, and almost the only interaction they had with locals was transactional. This type of tourism, which also happens at the luxury end of the tourism spectrum, and many places in between, perpetuates the “us” and “them” attitude — an attitude that historically included an attitude of cultural superiority from the foreign visitors.

Put the locals front and centre

In my early years of blogging, I often wrote about topics that questioned tourism such as Travel is an experience in perception and these posts, below, which I have compiled into this one post. I didn’t have a lot of traffic back then, and didn’t get a lot of interest or support for these posts that questioned the role of tourism in society. Several years ago I published Celebrating real women travellers — a call for diversity in travel. I was becoming increasingly concerned about a stereotype that was emerging as the influencer phenomenon began, a stereotype that didn’t include diversity.

But now there is a sea change in the air. I think there is a much better opportunity now — now that people are waking up — to making a difference in tourism. I hope in the post COVID-19 world, more people we realize we need a new era in tourism to overcome the problems of the past such as over-tourism, pollution, cultural imperialism, etc.

Personally, I would like to see a paradigm shift where the focus of travel and tourism is on locals sharing their culture. This is a very different than how travel is currently perceived. Today, travelers and tourists are essentially consumers, and travel is a commodity enjoyed by only a privileged few. The expectation is that the local community will make tourists comfortable and do what is needed to get their business — even if it means warping their own culture.

I would like to see travel in a new way, less as a luxurious commodity enjoyed by only a privileged few, and more of an activity that puts the local community and environment in the spotlight. With the local community and environment at the centre of travel, different decisions will be made — decisions that will benefit the planet, rather than just offering self-oriented satiation to the traveller. This is travel as a social activity that has connection and regeneration at its heart.

I would like to promote an idea of travel that is more selfless and responsible. With more thought to the impact we have — than to our own consumer-driven goals.

Breathedreamgo and responsible travel

I am proud that I have been committed to what is now known as responsible tourism from the very beginning, from when I launched this blog in 2009. To that end, here are some topics I have covered on Breathedreamgo over the years.

- Celebrating real women travellers

- Travel is an experience in perception

- Protecting Indian elephants

- Responsible Tourism Guide to India

- Responsible Tourism Guide to Thailand

- Best responsible travel products

- Ethical tourism and children

- Stunning offbeat destinations in India

- Undiscovered destinations in Asia

Getting to know “the real India”

ORIGINAL DATE: JULY 13, 2010

India is a vast and beautiful country, filled with world heritage sites, massive cities, sacred pilgrimage routes, tropical beaches, and snow-capped mountains. But along with the ubiquitous tourist draws such as the Taj Mahal, the forts and palaces of Rajasthan and the intricately carved temples of Tamil Nadu, India is home to a very well-trodden backpacking trail.

I get that backpacking is a great way for young people to see the world and the astonishing variety of cultural difference. But I don’t think immersing yourself in the backpacking culture, and sticking strictly to the backpacking routes and hangouts, as outlined in Lonely Planet and other travel guides, is the best way to get to know a foreign culture.

Aside from the benefits of getting to know a foreign culture — such as increasing your knowledge, self-awareness and perspective — there may be other good reasons for taking the road less traveled. The backpacking culture injects a foreign element, and the people of that culture morph around it because they know that, in spite of appearances, these young people come from rich countries.

There is a dark side to backpacking in developing countries. Drug use is one issue, and all the negativity it attracts. And there’s another, which my friends and family in India have brought to my attention. Some people in developing nations feel conflicted contempt for backpackers who wear dirty clothes and stay in cheap hovels because they think they are experiencing the “real” India or Thailand or wherever. They won’t express it directly of course, because these are usually the same people who are trying to make a living off of foreigners. Which is why they’re conflicted.

I feel sure the people of these nations would give anything to have the wealth and opportunities many backpackers were born into in their home countries of Canada, Sweden, Australia. So they don’t understand why rich young westerners want to come to places like India and pretend to be poor. In fact, even the poorest of the poor in India take pride in their appearance and would never let themselves look like some of the slovenly backpackers and hippies I have seen.

If the only local people you meet while you are traveling are the people serving you beer, you are not really getting to know the people of that culture.

I try to see everything in life as a learning opportunity – what is this event or experience trying to teach me? The longer I spend in India, the more I prefer to find the places that are less affected by the influx of tourists; I find I have a growing aversion to “traveler’s haunts” as I call them – places like north Goa, Pushkar, Hampi, Manali, Dharamsala and Pahar Ganj in Delhi. And maybe that’s part of the process, and part of the magic, of travel. The more you go, the more you want to know.

Authentic travel is about engagement

ORIGINAL DATE: JULY 6, 2010

India is one of those places where the question of authentic, or “real” travel, often comes up. I have heard backpackers say that Pahar Ganj – the backpackers ghetto in Delhi – is the “real India,” whereas the Delhi-ites I know have almost never been there, and would probably be happy if it was bulldozed.

My own feeling is that backpacker culture is an import, and far from being “authentic” or “real” has actually caused the local culture to morph around it. It unwittingly creates a scene in which local people learn to cater to foreign tourists. And thus you find the Pink Floyd Café in the sacred town of Pushkar, and foreigners happily sipping beer in a place that is supposed to be entirely free of alcohol.

Authentic travel in India to me is:

– sitting on the living room floor around an open fire during the naming puja (religious ritual) for Ajay’s nephew,

– going shopping for diyas (lights) and flowers during the pre-Diwali madness in Delhi with Ajay’s Mother,

– trying to wrap my head around teacher Swami Brahmdev’s answers during satsang (question and answer period – literally translated from the Sanskrit as a search for truth) under the mango trees at Aurovalley Ashram,

– watching the effect love and play has on the Tibetan refugee children in the Art Refuge program in Dharamsala: they become children again.

For me, “authentic” travel is about slowing down and engaging. The more deeply involved I am, the more “authentic” it is.

But my experience of travel in India is rooted in my involvement with an Indian family, and has given me perhaps a different lens through which to view India. When I first landed in India in December 2005, Ajay picked me up at the airport and I stayed at his family home. (I had met him through a mutual friend about 13 years earlier, in 1992, when he visited Toronto.) We fell in love about three days later, and I was lucky to be warmly welcomed into his family.

So I live with my Ajay’s Indian family when I am in Delhi and try to blend in as much as I can – I am essentially Indian in Delhi. I live in non-touristy south Delhi, wear Indian clothes, rarely see or speak to non-Indians and move around the city as a local, not as a tourist. But of course I am not Indian so there is bound to be moments of friction as I assert my individuality or need for privacy. (Luckily his family is very tolerant.)

But the moment I start traveling and staying in guest houses, I am perceived as a foreigner and I can really sense the difference. In Delhi, I feel like I have crossed the cultural divide; I feel accepted for who I am. But on the road, I feel a bit like a target. I can sense a slightly condescending attitude (until I say I am married to an Indian, and the attitude completely evaporates); and of course I am often confronted with what one pundit called the “white tax” – inflated prices for foreigners.

Personally, I don’t like being a tourist in India – probably because I do have the experience of being in an Indian family for much of the time I am there. But I don’t know how to get around it when I am on the road.

In the end, if you have a profound and meaningful – or fun and enjoyable – personal experience, who is to judge whether it is authentic or not? After all, reality is perception and travel is an experience in perception.

If you enjoyed this post …

Please sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!