The Crossing: A story of Varanasi

In Varanasi, where the veil between life and death seems very thin, a boat ride on the river can become a journey to the other side.

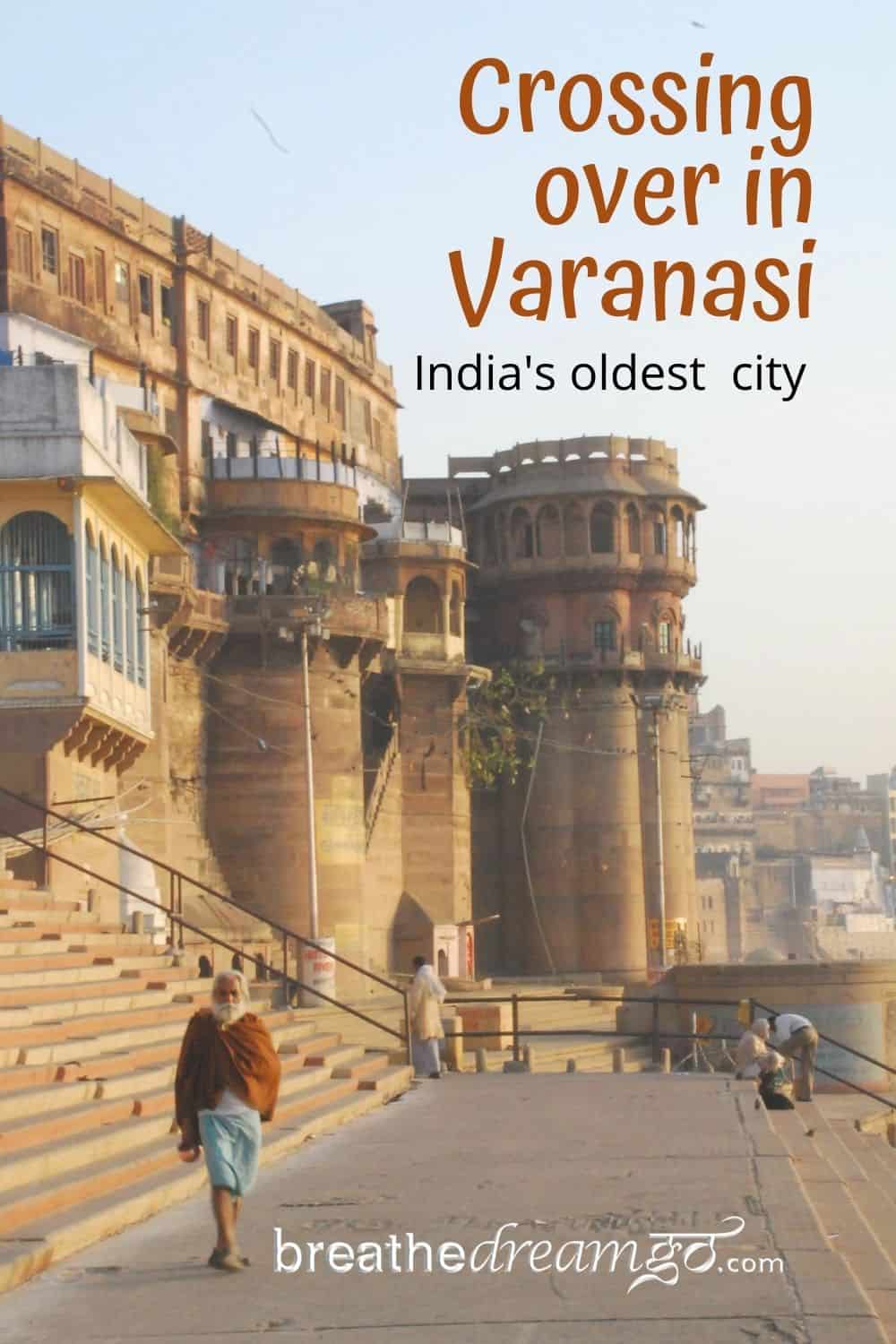

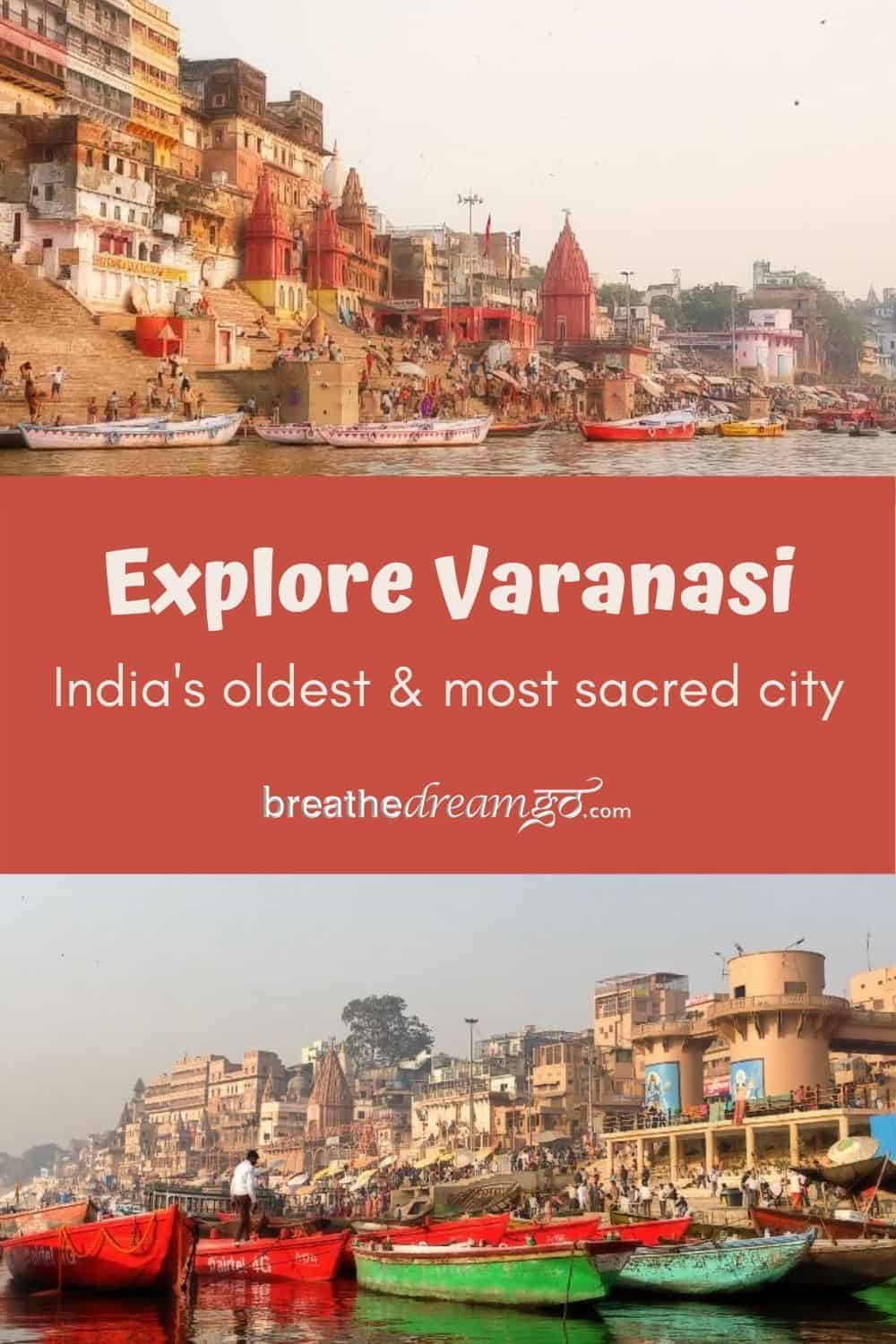

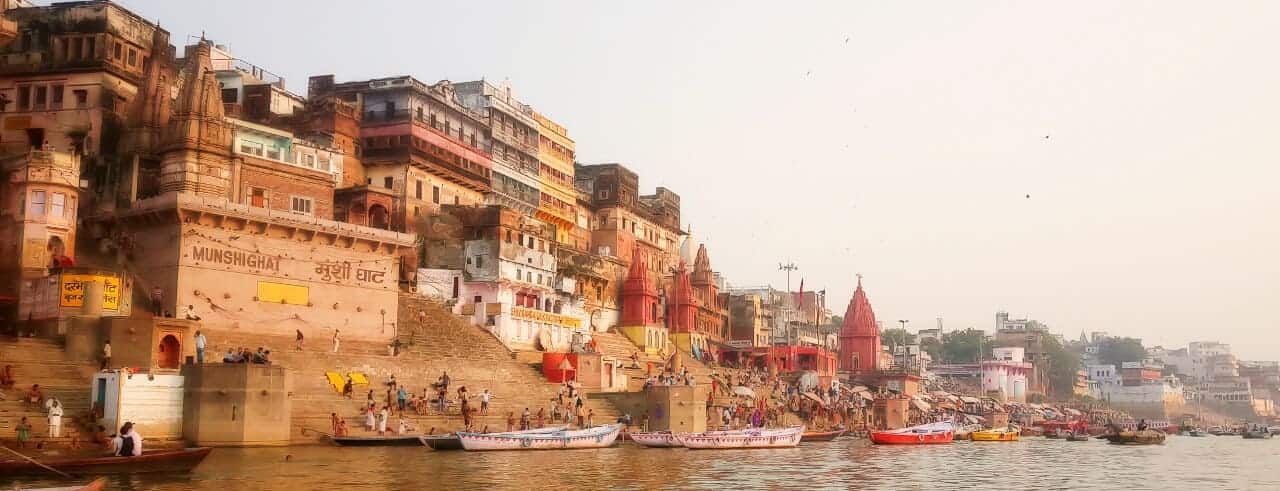

It was just before twilight when I stepped onto the creaky planking of a small wood boat. The old knotty boatman pushed us away from the muddy shore and started rowing. With each pull of the oars we crept along the surface of India’s most sacred river, past the scythe-like curve of ghats (steps) that line the western shore, towards Dasaswamedh Ghat, the main ghat, and the aarti (ceremony). The aarti is performed each evening at dusk to honour Ganga Ma, the Ganges River, mother of India. Behind the ghats, and a wall of soaring stone palaces and pavilions, pulses the abode of Shiva, the ancient, holy city of Varanasi, one of the oldest living cities on earth.

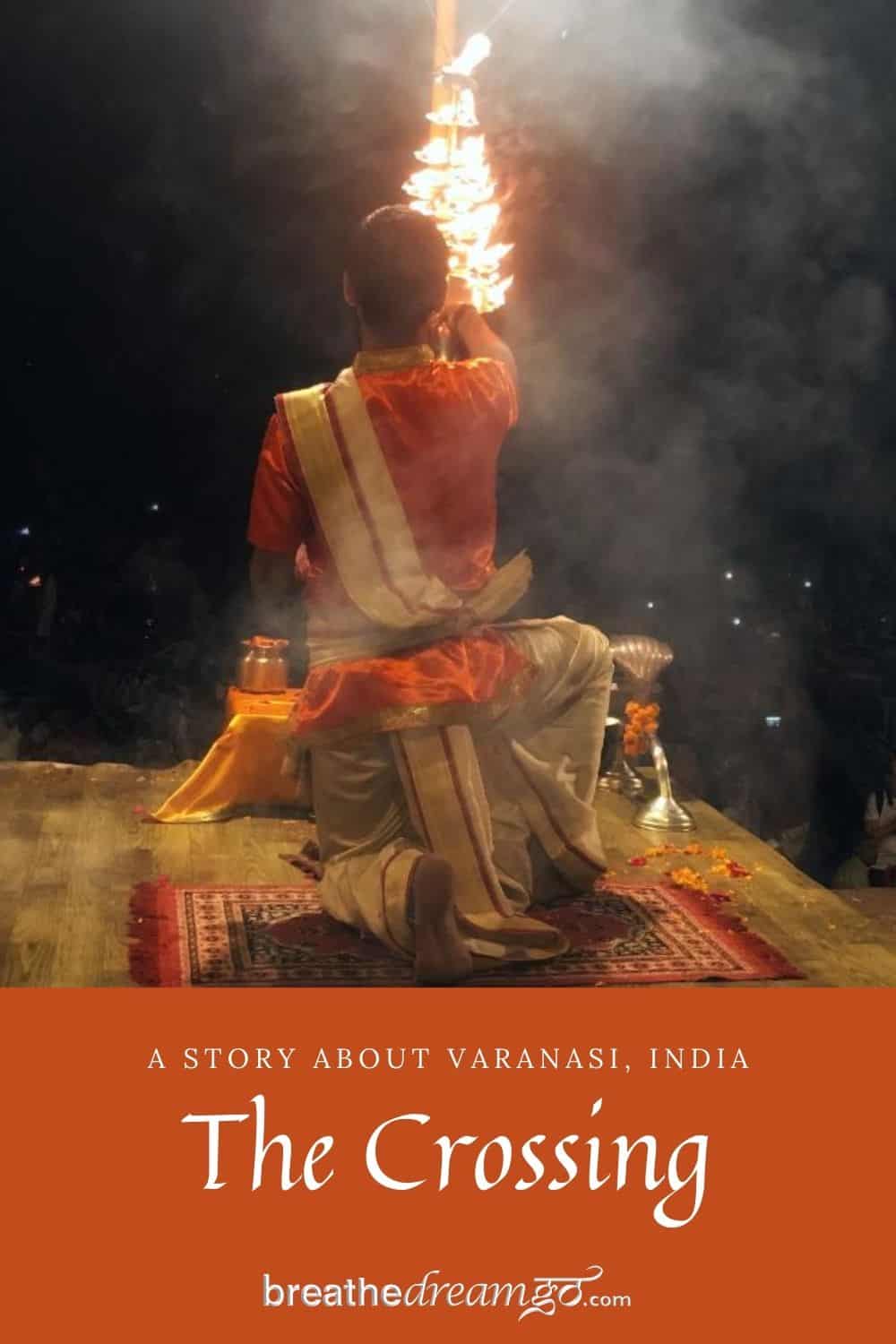

As the sky darkened, the moist air filled with swarms of mosquitoes, huge flying insects and the damp, putrid smell of the river. The riverfront darkness was broken at Dasaswamedh Ghat as crowds of people gathered to experience the aarti, performed by pandits (Hindu priests) in flowing robes brandishing huge burning diyas (brass candles) that sent bursts of light into the thickening dark. Loud music and chanting accompanied the choreographed ritual. I watched from my boat, tethered together with many other boats jostling their cargoes of Indian pilgrims and foreign tourists. I felt imbued with incense and reverence.

When the aarti ended, we untethered and continued to glide slowly north, the hypnotic current of the Ganga leading us along as we crossed the weakly lit ghats. Out of the darkness, a white shape appeared, wedged in the black water. Instinctively, I knew what it was and I froze. I prayed the boatman would not notice, would not point. I did not want it – he, she – pointed at; I did not want to be in collusion as a morbid voyeur. I wanted to observe the blunt presence of death, wrapped tightly in a white shroud and floating heavily in the Ganga, in the privacy of my own quiet contemplation. On we went, the boatman didn’t notice, and I started to breathe again.

Shiva’s dance of life and death

Varanasi is the city of Shiva, Hindu god of destruction, and his energy is intensely present. I thought about the figure in the river and felt shaken as some of my own fears were confronted and destroyed. I wondered if this figure recently one of the many dhoti- or sari-wearing pilgrims who I saw descending the ghats for ritual immersion in the sacred river – which they consider Shiva’s divine essence. Was he or she one of the unending stream of believers who have been making pilgrimages to Varanasi for 3,000 years, to seek salvation, to be absolved of sin, to become a jivan mukta – one who is liberated while still alive – or to die and cross over?

Crossing is a spiritual practise here in one of India’s holiest tirthas (crossing places). The souls of faithful Hindus cross to the other side in Varanasi, the most visited pilgrimage destination in all of India. To die and be cremated here helps to achieve moksha, a release from the continuous cycle of life-death-rebirth. Those who cannot afford a full cremation are released into the river as partially cremated corpses.

It takes a long time to cross the six kilometres of Varanasi ghats in a small boat. Finally we reached Manikarnika Ghat, the main cremation ghat, one of the oldest and most sacred ghats in Varanasi. It is said that Vishnu, the preserver, dug a well here at the time of creation and Shiva was also present. This ghat symbolizes the cycle of creation and destruction.

In most Indian cities, the cremation grounds are well-removed and hidden from view. But Varanasi is Mahashamshana, “the great cremation ground,” and death is ever-present. The burning bodies and hot ashes are a potent reminder that everything in the world is inevitably destroyed.

At any time of the day or night, Manikarnika Ghat is busy. As we passed very slowly –we were on our way back and traveling against the current – several cremation fires were in process and I clearly saw the bearded face of one man as the flames consumed him. Then I spotted another white figure in the river, but this time so did the boatman, who motioned excitedly. I was caught. The spectre of death would not let me look away.

Varanasi is a cauldron of Hindu beliefs made manifest. To be here is to burn. The careful avoidance of death practised in the west is burned away and the knife-like demarcation between this world and the next dissolves in an instant. It’s strong medicine and the effect can be shocking. And beguiling. Along with mourners, pilgrims, tourists, citizens and students, Varanasi seethes with wayward foreigners who wear layers of disheveled clothes and far-away expressions on their sunburnt faces.

Back to shore

I spent a week in Varanasi and often felt bombarded with intense energy and surreal disorientation. But then, on my last night I took a boat across the Ganga to the flat, wide sandbank on the other side to watch the sunset over the city and the ghats. Sometime after the sun disappeared behind the ancient buildings, the pink sky ebbed away leaving behind a pale glow that made the entire scene appear delicately soft, like a pale unearthly watercolour from a past century, or the dove grey underbelly of an iridescent bird. It was an indelibly beautiful scene.

The soft glow of the colours rendered the physical world – the palaces, temples, ghats, river – a ghostly mirage. Nothing seemed concrete; everything seemed to be gently pulsing with its spiritual, energetic essence. The veil between the worlds was obviously very thin at that moment, and I began to understand why this spot is considered so very sacred.

Lights began to appear and shimmer gently on the crystal surface of the sacred river and soon after the aarti began, way down the river at the main ghat. But I could hear the powerful chants and see the huge flames of the diyas from where I was seated on the sand, across from Assi Ghat. I felt in that moment in harmony with the rhythm of Varanasi. It is so peaceful on the sand bank, yet very few living souls cross over to the other side.

I lit two diyas that I had purchased from the urchins on the ghats, spoke the time immemorial prayer to the mother of India, Jai Ganga Mata, and set them afloat on the river in the twilight as the boatman rowed me back to shore.

Read more spiritual tales on Breathedreamgo

Background to The Crossing

This story was one of the first travel features I ever published. It was inspired by these photos, below, and published in The Toronto Star on August 28, 2009. I have lost the name of the photographer, but would like to credit him, and link to his work, so please contact me if you have any information.

If you enjoyed this post, you can….

Sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!