Table of Contents

Bhutan — Shangri-la 2.0

I almost jumped out of my seat when the pilot announced we were flying over Mount Everest. I was flying from Kathmandu to Bhutan, it was a clear day, and, lucky for me, I was seated on the left side of the plane — the side with the view — when the pilot said those magic words. In fact, we flew over four of the world’s five highest mountains, including Kanchendzonga, the massive five-peaked deity that straddles the border between Nepal and Sikkim. I really felt I was in heaven. Literally.

I have long been fascinated with Everest and drawn to the purity and grandeur of the Himalayas. It was the Himalayas — and the myth of Shangri-la — that drew me to Bhutan. The film (and book) Lost Horizon gave the world the term Shangri-la — and that film made a big impression on me as a child. It’s about a plane carrying several Europeans that crashes in Shangri-la, a Utopia hidden among the Himalayas.

Bhutan is often compared to a modern-day Shangri-la, owing to its pristine location, stable government and carefully preserved Himalayan culture. But it’s a remote, unknown, mysterious country, a country that few people visit, and I really didn’t know what to expect.

Bhutan gets only about 40,000 tourists each year, partly because there is a minimum spend required ($200 USD per day, rising soon to $250 USD) and partly because there are only two flights into the country each day, on Druk Air, the national airline. It’s a very mountainous country and there’s only one, short runway in the entire country. The descent is, um, memorable. Put it this way — the pilot felt compelled to make an announcement about how the “sharp left turn” needed to get around a mountain before landing was absolutely normal.

We landed safely and the door of the plane opened and I was excited by the anticipation of adventure. I felt very lucky to be in Bhutan, and it was all thanks to an invitation by the COMO-owned boutique hotel Uma Paro that made it possible. The Uma Paro is one of only two or three five-star hotels in Bhutan. Here is my post about the Uma Paro: Luxury in the Himalayas. You can read my experience of having a butler and my treatments at the hotel’s COMO Shambhala Spa.

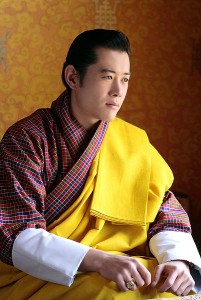

Bhutan is a small country (the size of Switzerland with a population of 700,000), located between India and China in the Himalayas, yet it comprises a surprising range of topographical and climatic variety, from snow-capped peaks to sub-tropical forests. It’s a Buddhist country with a forward-thinking, young monarch (the Fifth King, Jigme Khesar Namgyel Wangchuk) who brought democracy and a constitutional monarchy to the people.

Here’s an excellent photo essay, Bhutan crowns a new king, that was published in 2008 at the time of his coronation. The King is the head of secular Bhutan and the Je Khenpo is the head of the state religion, Mahayana Buddhism.

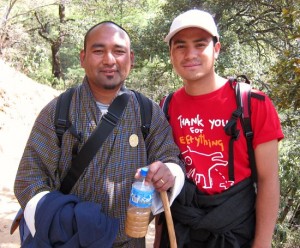

The first thing I noticed when I landed was that the all the airport buildings were built and decorated in the traditional Bhutanese style — it really must be one of the world’s most picturesque airports — and there was a picture of the King just about everywhere I looked. I found out later that ALL buildings in Bhutan must be constructed in the traditional style, part of Bhutan’s attempt to preserve their culture. I was greeted by Kanchzen, my guide, and David, my driver, and spent the next four days with these very nice men while I was out of the hotel; and with Jeewan, my butler, when I was at the hotel. Bhutan requires that every tourist have a guide, car and driver, and you really can’t move around without them. Bhutan does NOT require that you have a butler … but, oh, that they would. It was a wonderful treat to have a very polite and doting man waiting on my every request. I got used to it perhaps a little too fast.

The big tourist draws in Bhutan are the great outdoors and the traditional Bhutanese culture, and the country is known world-wide for an unusual governmental policy: the Gross National Happiness Indicator (GNHI). These three are intertwined, as preserving the natural environment and the traditional culture are two of the four pillars of the GNHI. (The other two are good governance and a balance of social and economic development.)

After checking in and having a cup of tea, the first thing I did was go for a walk with Kanchzen to see the view from the hill next to the Uma Paro, and to savour the sweet, fresh air. I took this photo, above, of a Bhutan-style inukshuk (an inukshuk is a term that comes from the Inuit in Canada) on that first walk. I think the air in Bhutan is the best I have ever inhaled and the mountain scenery is every bit as spectacular as you can imagine. I spent my scant five days in Bhutan in the Paro and Thimpu valleys, which are adjoining, so I only got to see one small section of the country, but it gave me a taste of Bhutan’s flavour and its style of tourism. Essentially, you can’t go anywhere without your guide, so no FIT — free, independent, travel — is allowed in Bhutan.

Touring the Paro Valley

On my second day in Bhutan, Kanchzen, David and I toured the Paro Valley. It’s not a big valley, everything is quite compact, but it contains a lot of history. We stopped first at an ancient monastery, Druk Choeding Temple, that was celebrating an annual festival. The sound of sonorous, hypnotic chanting, very much in the style of Tibet Buddhism, attracted me, and lots of monks and devotees, too. The monastery interior was very small, and held only about half the monks in attendance. The rest were seated in a tent on the lawn, and all the devotees were likewise seated on the lawn. Kanchzen and I stayed a long time at the monastery, first on the lawn and then in the main building, where the chanting was taking place. I found the atmosphere peaceful and and the chanting mesmerizing, and the warm sunny day was so conducive to relaxing on the grass among the people. I took lots of photos — the people didn’t seem to mind, they mostly ignored me — and I was delighted to be included when the monks were handing out money to everyone (they also handed out food, tea and water).

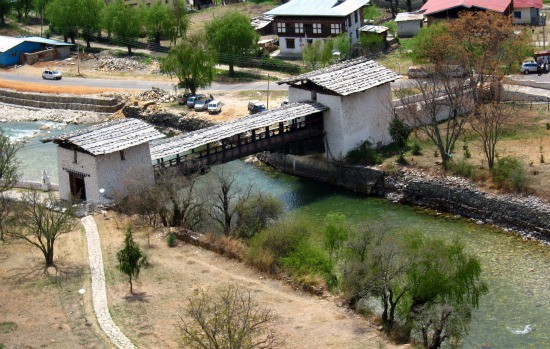

From there we went to the Paro Dzong. The Dzong is the main administrative building in each region of Bhutan, and the one in Paro is of historical significance. It is also a monastery, so it’s interesting to see bureaucrats and monks using the same facility, which I found to have a surprisingly serene atmosphere. The 16th century building was in the beautiful Bhutanese style of architecture and decor, and I loved the massively detailed, colourful murals of demons, gods and mandalas that line the entrance hall. They were very fine examples of Vajrayana art, the didactic art of Buddhism. One mandala depicted the various levels of spiritual consciousness, with rapes and murders at the bottom, scenes from household life, such as giving birth, in the middle, and saintly pursuits such as praying and giving alms to the poor at the top. I also enjoyed finding a small wooden balcony in the corner of the monastery part of the building, with a sweeping view of the Paro river and valley below and a game board etched into the wooden floor. This was obviously where the monks relaxed when they weren’t busy with their studies or duties.

Everyone at the Dzong was wearing traditional Bhutanese clothes. It is mandated by law that men must wear the gho (knee-length robe) and women must wear the kira (skirt and jacket) during working hours. When we went into the Paro Dzong, Kanchzen also had to wrap a long white scarf around himself, which is the Bhutanese version of the neck tie, and must be warn in official circumstances. As in many traditional cultures, respect for authority, and for elders, is very important

From the Dzong, we walked down a winding path to the river and crossed a picturesque covered bridge. On the far side, our driver David picked us up and drove us into town. Paro is not a very big town, population is only about 4,000 or 5,000, but it does have a respectably sized commercial centre, and of course all the buildings and stores were in the traditional Bhutanese style. We stopped in town and ate at a restaurant — the only other people eating there were tourists — but the food is not worth writing about. After the cuisine of India, it is simple and the spicing seems … odd … though the famous chili-and-cheese dish was quite good, and almost spicy enough for me. (I’m an aberration among westerners, I like spicy food to be very, very hot!) I wandered into some of the shops, but bought only a lacquered bowl, the kind the monks use to drink tea. It is my souvenir of Bhutan and will remind me of the lovely morning I spent with Kanchzen at the monastery, listening to the peaceful chanting and feeling the warm sun and temperate breeze on my face. Definitely one of my favourite memories from Bhutan. After shopping, Kanchzen and I decided to walk back up to the Uma Paro, which is on a hill side outside of town. I was planning to go to Taktshang (Tiger’s Nest) Monastery the next day, and this was my warm up climb.

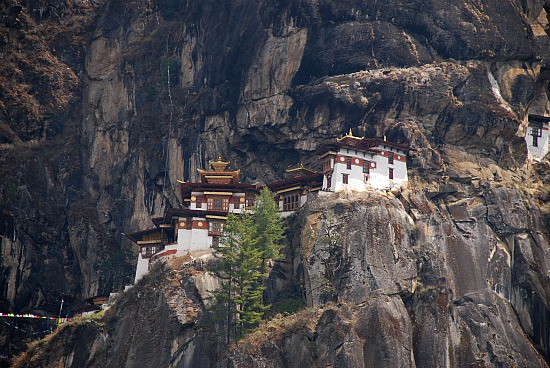

Happiness is a place between too much and too little

Up to this point I felt great, and barely noticed the high altitude. In fact, though Paro is in a valley, it is still at a much higher altitude than what I am used to. But I woke the next morning at about 4 or 5 am feeling wretched. I was running to the bathroom and feeling as if I had a bad case of both Delhi-belly and altitude sickness. All I could think about was that THIS was the day I was supposed to climb 1,200 metres to Taktshang Monastery, my only opportunity, and I didn’t want to miss it. Taktshang Monastery is the Taj Mahal of Bhutan. It is the country’s leading tourist attraction and a very important sacred site — a monastery built along a cliff face, high above the valley floor, to commemorate a mythical / historical event: it is believed that Guru Rinpoche, the founder of Buddhism in Bhutan, flew to this cave on the back of a tigress in the 8th century. The monastery was built in the 17th century.

I kept up a running conversation in my head for hours — I can make it if I try; there’s no way I can make it, I will collapse — until David and Kanchzen arrived to get me at 8 a.m. They were shocked at my ghostly pallor and also at my steely determination to at least try. So, we drove to the foot of the mountain, and David decided to walk with us, just in case. I was glad he was there — two men to carry me down if I collapsed! In fact, David helped hold my hair out of my face when I vomited by the side of the trail, and he and Kanchzen proved to be understanding, gentle and steady guides as I forced myself up that steep trail, step by agonizing step. Jeewan, my butler, had done his part too, by providing me with a pack containing bland foods, ginger tea and an electrolyte drink, which David and Kanchzen carried, of course. They also carried my cameras. Several grueling hours later I had made it only to the rest stop, which is about three-quarters of the way up, and directly across a chasm from the monastery, but that was the end of that. I couldn’t make it any further.

I thought a lot about happiness and about the spiritual lessons of my pilgrimage to Taktshang as I walked. Bhutan Tourism uses the tag line, Happiness is a place, which is a shortened version of a Finnish proverb: Happiness is a place between too much and too little. I think this very slow walk up the mountain was teaching me to slow down, to appreciate the journey and to be content with reaching the halfway point — the place between too much and too little. I have been really pushing myself, working very hard, very long hours and trying to attain certain goals. This walk was a reminder. It also made me appreciate all the help I got to get up that mountain — from Kanchzen, David and Jeewan to the mantra, written on a tiny scrap of paper, that blew in on the breeze and landed at my feet. The mantra reminded me of the divine help I was getting. I let go of the goal of reaching Taktshang, and instead enjoyed the journey, and felt very grateful for the experience.

My final day in Bhutan was spent in Thimpu, the capital, where I interviewed two people about Bhutan’s Gross National Happiness Indicator (for an article I am writing), met with a man from the Tourism department and had lunch with Nancy Strickland of the Bhutan Canada Foundation, at her home. I will write another blog about the GNHI, but here I would like to mention the good work that the Bhutan Canada Foundation (BCF) is doing to provide Bhutan with Canadian teachers and help improve standards of education in the country, especially in the remote regions of the south and east. The BCF grew out of the efforts of Canadian Jesuit priest Father William Mackey, who helped set up the modern education system in Bhutan in the early 1960s and lived in the country for more than 30 years, until his death in 1995. He is a kind of Norman Bethune figure in Bhutan — and has made it a great place for Canadians to visit because he is so honoured and appreciated. I really enjoyed visiting the BCF offices, and seeing a “shrine” to Father Mackey along one wall.

What’s Bhutan really like?

As I was driving, with Kanchzen and David, along the winding highway between Thimpu and Paro, I saw a number of women selling big, green stalks of fresh asparagus by the side of the road. This tasty vegetable, one of my favourites, was obviously in season, but the only time it was served to me was on the plane back to India, in a tiny dish, covered in cellophane. The three tiny pieces on my plate was barely enough to give me a taste — between too much and too little, the serving size erred on the side of too little. This is a bit like my experience of tourism in Bhutan.

I don’t mean any disrespect. In fact, I totally respect Bhutan’s efforts to preserve its environment and culture. Thimpu had one traffic light, but they took it down and put back the traffic police in the centre of town. I think that’s just great. Don’t get me wrong. But I think I need more time in the country, and I would really like to wander about, occasionally, without a guide. I’ll be good, promise.

In the end, though I was very sad to leave, especially so soon after arriving; and though I knew I would sorely miss that fresh air … honestly … I was kinda looking forward to diving back into the freewheelin’ chaos of Delhi. But maybe that’s just me. Maybe I would be the guy who wants to leave Shangri-la at the end of the movie/book, and not the guy who wants to stay. Or maybe my idea of Shangri-la is just a little different.

[DISCLOSURE NOTE: While in Bhutan, I was a guest of the Uma Paro. But as always, views expressed are my own and are in no way influenced by accepting a press trip. I will not compromise the editorial integrity of Breathedreamgo.]

If you enjoyed this post, please sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!