Table of Contents

Unravelling the mystery of Mirabai

In the final part of the Mirabai Expedition, I follow her footsteps to the seaside town of Dwarka where she disappeared while singing in the temple, leaving only her sari wrapped around the Krishna murti

THE LONG DRIVE ACROSS flat, featureless and very hot west Gujarat is broken only by a stop at a business hotel, inexplicably located in the middle of nowhere. We stop for chai and pakodas, in an empty, airless, and featureless hotel coffee shop. The only guests appear to be two Japanese business men, so surreally out of place, I think, “of course.”

Read the Mirabai Expedition series:

Part 1: Walking in the footsteps of Mirabai

Part 2: Uncovering the feminine in Merta, Rajasthan

Part 3: The footsteps of royalty in Chittorgarh, Rajasthan

Part 4: Releasing the bonds of love in Dwarka, Gujarat

The last stage, a four-hour drive from Rajkot to Dwarka, offers almost nothing of interest to grab my attention except huge industrial and manufacturing plants. My interest in Dwarka suddenly perks up, though, as we drive pass a salt flat and a herd of camels. As we cross a river, the road runs up a small rise, and the town is suddenly visible, laid out in front of us, with the Dwarkadesh (Krishna) Temple rising above it. We stop so I can take a photo, and the panorama makes me think of the Wizard of Oz and the approach to the Emerald City. Except on a humble scale.

In this remote seaside town of Dwarka is one of the most important Hindu temples in India, and one of the most important Krishna Temples. This is where Mirabai’s story ends, where she mysteriously disappeared in front of crowds of people, while singing in the temple to her beloved Krishna, when she was about my age.

And this is where I wonder how my story will end.

Dwarka is a flat place, very barren, washed by sun and sea … but very light. The light here has a crystal clarity, and the colours are few: beige sand, blue sky, silver sea. I feel very calm here, and obviously Indians do too, because the frenetic pace of most Indian towns is almost non-existent here.

Though a small town, Dwarka is awash in temples, new and old, grand and modest. They are everywhere. But the 5,000 year old Dwarkadesh Temple in the centre of town towers over all of them. Like a medieval cathedral town, everything revolves around Dwarkadesh Temple, which emanates an ancient, deeply reverent feeling.

Aside from it’s seaside location and prominent temples, Dwarka is a modest town of narrow, winding, colourless streets and the usual conglomeration of shops, stalls, cows, sadhus, beggars, cyclists, two-wheelers, autorickshaws and the like. But the pace is slower and the sea air gives it a special quality.

Miracles begin to happen

I like Dwarka instantly, though it is far from beautiful. My hotel faces the sea, otherwise it has nothing special to recommend it; a characterless box with awkward young men working behind the desk and in the restaurant. The sea front here is lined with concrete, dotted with temples and besmatterd by cow dung. It is not what a westerner would call picturesque.

It was just down this coast, about 70 kilometres away, that Mahatma Gandhi was born in Porbandar.

After checking in, the first thing I do is ask one of the young men behind the counter if there is a local guide who can help me learn about the temple. He says there is one priest who speaks English and he will call him. I go back to my room with my expectations in check. After five minutes, I get a call from the front desk. The priest has arrived.

The first miracle.

To say I am surprised to find a handsome, charismatic young man in a crisp, clean, silk dhoti, who speaks almost perfect English, waiting for me is a gross understatement. If I had planned ahead, I would never have met a better guide than Hardik Dwarka. Not only does he speak English, he has a sophisticated understanding of the world and he is from the Googly Brahmin caste that has served the Dwarkadesh Temple for hundreds of years. I immediately sense that Hardik is a special person … and my short association with him proves this to be true.

Hardik and I arrange to meet at 5 pm, when the temple reopens, and he is right on time. The second miracle.

Meeting Mirabai at the end of her story

My driver Gopal drives Hardik and I first to the Meerabai Temple in the centre of Dwarka. It is a very modest temple in the market area, and you would never find it without a guide. Hardik tells me it is very new, and was built by Sadhri Devi and her followers from Nagor, Rajasthan. While I am pleased to find the Meerabai Temple in Dwarka, I do not get any particular feeling from being there. Mostly, I am pleased to see women celebrated — Sadhri Devi also seems to be a musician.

From there, we drive through the dusty, streets as Hardik explains that Krishna lived for 100 years in Dwarka. He came here for the quiet, and there is still a sense of quietness about this sacred town. Krishna built Dwarkadesh Temple 5,000 years ago. The name means:

Dwar = gate or entrance

Ka = moksha

Gopal drops us outside the temple compound, where people are gathering. Beggars line the outside wall, flower and tulsi sellers walk around with garlands, hawking their wares, and large groups of pilgrims arrive with anxious excitement evident in their behaviour. We walk very slowly through the crowd and as Hardik speaks, I became aware only of his presence and his words. He completely holds my attention, even in the madding crowd.

“Krishna is awareness,” Hardik says, “He teaches us that the past and future is not real. Only now is real.” For the first time, I feel like I have found a way to understand Krishna. Maybe someone said this to me before, but at the Dwarkadesh Temple, I finally heard. All the many years I studied and practised Gestalt and then yoga, I was also trying to understand this teaching. Hardik makes Krishna accessible and real to me.

I ask him about Mirabai.

“Mirabai shows us a different way to love. In her love for Krishna, she didn’t want anything. In reality, lovers are always givers and takers. Mirabai’s love for Krishna was amazing. There were no boundaries, she forgot herself. The saints told her that her love was very powerful.”

Krishna is awareness and Mirabai is love.

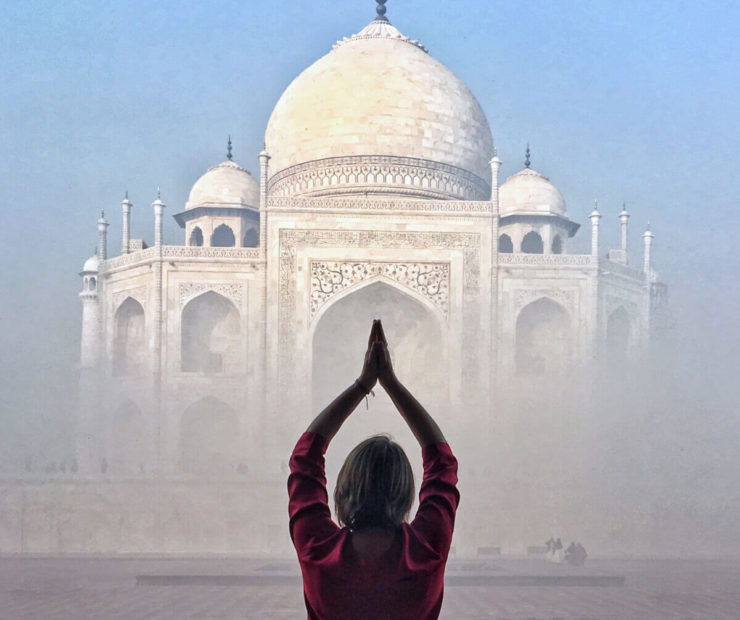

We drop our shoes and my camera at a counter, and enter the temple. I immediately feel I am surrounded by ancient, sacred energy and know this is a special place. The spire of the temple towers above us, covered in ornate carvings, topped by a bright silk flag fluttering in the sea breeze.

Hardik takes me directly into the heart of the temple, the inner sanctum, to see the black figure of Krishna, bedecked in colourful garments, deeply set in a recess, and surrounded by several frames of gold and silver. Two queues of anxious people, male and female, are corralled by metal gates and pressing against the barrier for darshan, to see the figure of Krishna.

I find the darshan to be a bit overwhelming and am happy to move out of the main temple and walk around the compound. Several other smaller temple structures, all ornately carved long, long ago, surround the main building in close proximity. It is all made of grey stone burnished by eons, and has a distinctly medieval feeling. In fact, they are constantly repairing and replacing the stone as it gets eroded by the salt air so nothing is as old as it looks or feels.

As we talk about Krishna, Mirabai, Hinduism, spirituality, religion and our own lives, we make our way around the temple, and to the back of the darshan lineup. On a raised marble platform in front of the temple dedicated to Krishna’s real mother, I can see above the pilgrim’s heads into the inner sanctum. I am completely surrounded by the womb of the temple and stand happily, imbibing a feeling of calm, and imagining Mirabai singing her love for Lord Krishna on this very spot. Here was the place she disappeared.

When I first conceived of the Mirabai Expedition, I hoped to, perhaps, find out exactly what happened to her at the Dwarkadesh Temple. I thought perhaps I would become a sleuth, digging up a medieval mystery, and solving finally solving it. Somehow.

I ask Hardik about the disappearance, and he says that only a small square of her sari was left and that it was placed on the Krishna statue.

In my research, I learned she was drawn to Dwarka by the extreme sanctity of the Krishna temple, and she was perhaps also running a soup kitchen for the poor at the time of her disappearance.

The spiritual tradition is that she dissolved into love for Krishna. But others, less mystically inclined, say she fled from her fame. Apparently, a delegation was sent to Dwarka to persuade Mirabai to return to Chittorgarh because of either a political situation or drought. By this time, she was about 50 (one account says she was 54, which is my age) and famed for her ardent devotion and beautiful poems and songs.

She may not have wanted to return to Chittorgarh, for obvious reasons — her in-laws had tried to kill her. Perhaps she decided to leave her identity behind and run away. Or perhaps she did undergo a spiritual miracle.

Seeing my mother’s eyes

It’s my second morning in Dwarka. I meet Hardik again, at 6:30 am, and we go back to the Dwarkadesh Temple. This time, we walk down to the ghats on the river, and watch the sun rise as pilgrims bathe and hordes of cows walk the streets. He shows me around several other parts of the temple, including the room where people are weighed on a large scale. People donate their weight in grain to the community, to feed widows, priests and to provide the grain for prasad. They sit on a scale, and five types of grains, in sacks, are loaded up to equal the weight.

We go into the temple compound where I join the queue for darshan. A woman in a mauve sari pushes me several times, though I motion for her to stay calm, to wait her turn. She pushes again and I say in English, knowing she will not understand, “Where do you think god is? You think god is only up there?” She ignores me, but the woman behind her understands, and makes room for me. So I let the pushy woman go ahead, and then enjoy the space created by the understanding woman, recognizing that I am experiencing the flow of consciousness.

Afterwards, I go back to the spot at the back of the queue, on the raised dais, and stand again feeling the subtle energy. I feel a kind of buoyant joy undulating through me, from where my bare feet touch the smooth, cool marble floor all the way up through my body to the top of my head. It is a pleasant feeling, like bobbing on a summer lake.

I hesitate leaving as I am enjoying the feeling and being in this womb-like temple. In fact, I can imagine never leaving. But eventually I do, and we walk out, pick up our shoes and again enter the stream of life, the field of time and space.

Walking to where Gopal is waiting by the car, an old, bent woman in colourless rags holds out a cup towards me begging for money. This happens all the time in India, and I have learned to harden myself against it. But this time, my heart is open and I want to give her something. I have no money with me, but Hardik gives me a small bill and I hand it to her. Our eyes meet and hers are filled with love.

I am stopped in my tracks. I feel overcome with emotion, and start to cry. Hardik asks me if I am okay.

“I saw my mother’s eyes in hers,” I blurt out.

I can barely move. Waves of love, longing and grief wash over me. I lost my mother 16 years ago, and all the pain, and all the love, come rushing back. I have to stop and lean against a wall, letting the masses of cows and pilgrims pass in a blur. An eternity of time opens up. I am in distant Dwarka and I am at home in Canada. I am here and now and with my mother in the distant past.

And then, all of a sudden, I have the key to the Mirabai story and the mystery of what happened to her doesn’t matter to me anymore.

The key to the Mirabai story

I know what Mirabai’s essence was, what the key to her story is, and what I am meant to learn from this expedition. And I can say it in one word.

Love.

Love is all that matters.

Krishna is awareness and Mirabai is love, and together they merged. This is our higher self. This is the story of Mirabai.

But there is something else, too.

That evening, Hardik and I go to the seaside to watch the sunset, at the western-most point of India.

Hardik and I talk about our lives and about the idea of following your heart and listening to your inner voice, as Mirabai had done. (And, indeed, as Mahatma Gandhi had done, too.)

He tells me he had married for love, and risked everything. Because of family disapproval he and his wife and two children live alone in a tiny house with no windows. He tells me he had an IT job he loved in booming Hyderabad, but came home because his father was sick and needed him. Now he feels cut off from the world in a small, remote seaside town. He tells me he followed his heart and believed in love. No, he didn’t tell me this part, he didn’t have to.

Then, after a pause, he asks me why I am interested in the story of Mirabai.

I say, “because of what you just said.”

Silence.

We listen to the ocean waves, the call of the birds, the devotional music floating on the warm sea breeze. In silence we feel the bonds of love, freeing our souls to soar together and alone, one and oneness.

If you enjoyed this post, you can….

Sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!