- The legend of the Titanic lives on

- The Titanic and what it means

- People of Halifax are Titanic heroes

People of Halifax are Titanic heroes

Table of Contents

Shroud of Titanic woven into fabric of Halifax

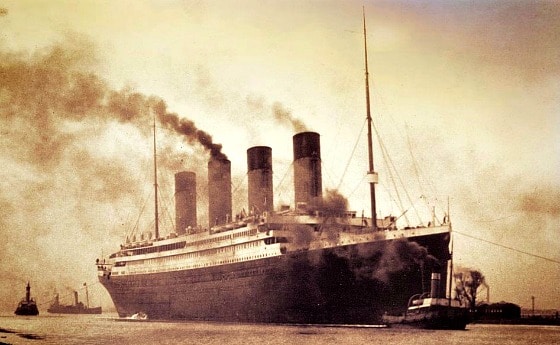

Before I went to Halifax for the Titanic 100 commemoration events, I didn’t get it. I didn’t really get the full impact of the loss of more than 1,500 people when the ship sank on April 15, 1912 after striking an iceberg about 600 kilometres off the coast of Newfoundland. I didn’t get that the crews of two Halifax-based cable ships, the Mackay-Bennett and the Minia, unhesitatingly made for the wreck site on April 17, two days later, after being contracted by the White Star company. I didn’t get that these men braved the cold, choppy waters of the North Atlantic to pull 302 dead bodies — one of them a 19-month-old baby — into small boats lowered from the cable ships for the purpose.

This photo, above, is now the enduring image for me of the epic disaster. It has replaced photographic images of the great steamship leaving Southampton and of Captain E.J. Smith standing on the bridge. It has replaced the drawing of the Wallace Hartley band playing on the deck as the ship sinks in my old Titanic book and computer generated images of the Titanic breaking in two before slipping beneath the waves.

After spending the Titanic 100th anniversary weekend steeped in the historic port city’s many connections to the world’s most famous shipwreck, interviewing Titanic experts in Halifax, attending the Night of the Bells Titanic 100 anniversary event on the evening of April 14 and the spiritual ceremony at Fairview Lawn Cemetery on April 15, where about 120 Titanic victims are buried (including the 19-month-old “Unknown Child,” J. Dawson and John Law Hume, the band’s violinist) — I now have a much better understanding of Halifax’s deeply etched connections to the shipwreck. And I now feel that the people of Halifax are Titanic heroes — especially the crew and undertakers aboard the Mackay-Bennett and the Minia.

The City of Sorrows

Kipling said it best when he said that Halifax is “the warden of the honour of the north.” The port city on the edge of the tumultuous North Atlantic is long accustomed to maritime rescue and recovery operations. But of course the sinking of the RMS Titanic is the most famous maritime shipwreck connected to Halifax.

New York was where they brought the 706 survivors, aboard the Cunard liner Carpathia. About 10,000 people waited dockside in New York for the Carpathia to arrive. Halifax was where they quietly, and in secrecy, brought the victims, the bodies picked up from the rough seas, kept afloat by their cork life preservers. When the body of the baby floated “face up” towards the boat, it brought hardened seamen to tears. The 75-man crew of the Mackay-Bennett paid for a funeral and headstone for the child, who was buried with ceremony in the grave of the Unknown Child (recently identified as Sidney Goodwin).

I spent my first day in Halifax touring some of the approximately 45 Titanic-related sites in the city, and interviewing people about Halifax’s connection to the tragedy.

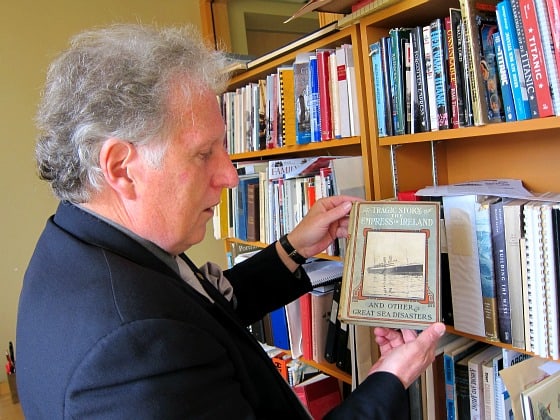

Garry Shutlak is the Senior Reference Archivist at the Nova Scotia Archives and he is a Titanic subject expert who not only has bookshelves full of Titanic books in his office — he even lives in a flat in the home of Titanic victim George Wright. Garry has an encyclopedic knowledge of Halifax’s Titanic connections, but during much of our talk he stressed that Halifax has a history of helping out in the wake of disasters and that Haligonians are proud of their role. “We like to help,” he said. He also talked about how the Titanic connections are woven into the fabric of the city. Growing up, everyone had a frame made from Titanic driftwood, or was related to a passenger or one of the crew of the rescue and recovery ships, or lived or worked in a building associated with the Titanic.

It was Garry who first impressed upon me Halifax’s role in maritime rescue and recovery. Here he is above holding a book about another major shipwreck that Halifax assisted, the Empress of Ireland. The Nova Scotia archives has a lot of resources about the Titanic, including fatality reports and a virtual exhibit.

My next stop was the Bedford Institute of Oceanography to meet with marine geologist Steve Blasco. Steve was the chief scientist on a Canada-Soviet joint expedition to the Titanic wreck in 1991 and went down for 17 hours to study the ocean floor. Steve gave me a tour of the institute’s permanent Titanic exhibit and explained to me the important scientific findings that resulted in his expedition to the Titanic “grave” site — including a new understanding of the dynamic nature of the deep ocean, and how Titanic is now part of an ocean floor ecosystem. The photo above is of the bridge, before the sinking and now, 100 years later on the ocean floor. It demonstrates the ship’s transformation by the living waters.

Steve was instrumental in supporting the Robert Ballard expedition that discovered the wreck in 1985 — in fact the idea was born during dinner at Steve’s place in Halifax. He also helped Canadian film director James Cameron build a model of the bow section for use in creating accurate sets for the blockbuster movie. When I asked him what it was like to explore the massive wreck, the scientist turned very human and he told me how surprised he was by his emotional reaction to seeing the great ship through the tiny porthole of the submersible.

The flare heard round the world

All of the events I attended in Halifax were interesting, moving and well-presented, including the permanent Titanic exhibit at the Maritime Museum of the Atlantic and a fashion show I saw there — put on by the costume students at Dalhousie University. Each student chose a Titanic passenger and spent a year researching the woman, creating a gown based on real 1912 designs, and assuming the character of that passenger in the fashion show. It was a fascinating evening, and the clothes were gorgeous.

I also ate Titanic-themed dinners at restaurants in historic buildings. On Friday night, I ate a Titanic dinner at the Five Fishermen. This restaurant is housed in the former Snow Funeral Home — where the bodies of the first class passengers, including John Jacob Astor were taken. The staff there told me the building is haunted by two ghosts, and one is a little girl who died aboard the Titanic. The best dinner I ate was at the Press Gang, in one of the oldest buildings in Halifax.

There is no doubt that the people of Halifax have a genuine and heart-felt connection to the Titanic story, and it is not just because of the anniversary. There was a mournful, haunting feeling at many of the events, which cannot be artificially produced.

“For Halifax, the City of Sorrow, the Titanic continues to loom large … told in the story of the grave stones of those 150 who perished on this day a century ago. Halifax can be proud of that she played her part well from beginning to end … with dignity, care and compassion.” — Night of the Bells

[DISCLOSURE NOTICE: I was a guest of Halifax and Nova Scotia Tourism and stayed at the Westin Nova Scotian, where each morning I had a sunrise view of the harbour. Lovely. But as always, views expressed are my own and are in no way influenced by accepting a press trip. I will not compromise the editorial integrity of Breathedreamgo.]

If you enjoyed this post, please sign up to The Travel Newsletter in the sidebar and follow Breathedreamgo on all social media platforms including Instagram, TripAdvisor, Facebook, Pinterest, and Twitter. Thank you!